It was October, 1955, a week or so before my twelfth birthday. My mother and I, my three year-old sister, and my grandmother — who’d been living with us at that point for several years — found ourselves on final approach to a late-night landing in Paris.

We weren’t supposed to be landing in Paris. We were supposed to be landing in Frankfurt am Main en route to a reunion with my father at his new army posting in southwestern Germany. That, at least, was what was printed in our official travel orders. Now there was to be at least another day added to our schedule. The captain of the government chartered Seaboard and Western Constellation we’d first boarded early that morning in New York had just announced over the cabin intercom that since Rhein Main airport in Frankfurt was completely socked in, he was diverting our flight to Orly, the nearest international airport still clear of fog. So, like it or not and ready or not, we were now headed not to Frankfurt but to Paris, the magical Cité de la Lumiere that so much had been written about. My grandmother had taken me to see an American in Paris when I was eight, but no one had ever so much as hinted to me that Paris was a place that I might one day set foot in myself.

It was nearly midnight when we finally touched down on the runway at Orly. After the ceremony of deplaning, the guided trudge through the terminal, and half an hour or so of rummaging in purses, fumbling for passports and travel documents, and whispered negotiations incomprehensible to my not quite twelve year old self, we were bundled onto a dilapidated bus and ferried to our hotel through a mist-shrouded, and by this late hour largely extinguished City of Light.

Our hotel turned out to be the Hôtel le Littré, a modest establishment situated on the Rue Littré, less than a mile from the heart of Montparnasse, not that any of us had a clue at the time exactly where we were, or how improbable it was that any of us should have fetched up there at all, let alone by accident, let alone in the middle of the night. Standing in the lobby, with my ears still throbbing from the noise and vibration of the engines during our long flight, my first impression was of a somewhat muffled, somewhat claustrophobic lounge, with brocaded furnishings reminiscent of pictures from one of my grandmother’s old photograph albums.

While my mother was simultaneously engaged in juggling my sister and signing the register, a tiny, ancient-looking woman at the equally tiny front desk handed my grandmother a pair of the largest keys I’d ever seen. They were formidable, these keys, as though originally tasked with unlocking some ancient fortress, an impression enhanced by the fact that each was attached to a half-pound oval of brass with a number engraved on it. Looks more like a cell number than a room number, I remember thinking.

Mais non, my grandmother explained to me as we were being led upstairs to our rooms, such keys were not at all weird. Because it was customary in France to leave your key at the front desk when you were away from your room, and to pick it up when you returned, there was no need for it to fit into a pocket or purse. Besides, she said, the bigger and heavier a key was, the less likely it would be to wander off by itself. How she came up with this, I had no idea, but it sounded plausible, and my grandmother, who had been a world traveler with her father as a young girl, had never been the sort of person to make stuff up.

Okay, then. Maybe French keys weren’t actually so weird after all, but they weren’t the only things French that seemed weird to me that evening, and I was far from done pestering people for explanations. Why was it so warm in our room, I demanded, why were there half a dozen pillows and almost that many rolled-up (rolled up?) quilts piled on the beds when it was already so warm, and what was that thing in the closet off the bathroom that looked like a toilet, but wasn’t? (My utterly exhausted grandmother sighed and rolled her eyes at that last question, and then, with a perfunctory nod to her daughter, got up and padded silently, shoes and overnight bag in hand, to her own adjacent room.)

The next morning — very early the next morning — we boarded the same dilapidated bus that had delivered us the night before, and set off again, still somewhat bleary-eyed, for the airport and the final leg of our journey to Frankfurt. As we crept through the slowly awakening city, there was still little to see, but I marked the cobblestones, the improbably broad streets, and the middle-aged men with rolled-up sleeves and calf-length white aprons cranking out awnings and arranging chairs and tables on the sidewalks. Sidewalk cafés, I suddenly realized, sidewalk cafés just like in the movies.

Then, as we turned a corner, there it was in the middle distance, floating above the rooftops and autumn foliage of the city, the upper two-thirds of la tour Eiffel. This, somehow, was not just like in the movies, this was more like the word made flesh of religious hyperbole, and I was motoring away from it like a soul being banished from paradise.

The moment didn’t last. I was a little more romantic, a little more literary at twelve than the average American kid, I suppose, but I was still a kid, and I liked airplanes and adventures too. I was really looking forward to trying out my ten words of German when we finally got where we were, after all, supposed to be going.

I’ve never returned to the City of Light, not once in the 65 years since I saw it for the first and only time just as the first rays of dawn were beginning to filter through the autumnal branches of the trees lining its famous boulevards. Even so, I suspect that I’m as glad as any Parisian is that it’s still there, and that it’s still Paris. Some places, Grâce à Dieu, are eternal. Paris is one of them.

Optimism is rarely a completely honest emotion, and pessimism often seems an order of magnitude too facile to be taken seriously. Realism, at least the realism practiced by its self-described and insufferably self-righteous adepts, lacks respect for those subtler aspects of reality that an attuned consciousness can perceive, but never adequately describe — except perhaps through the approximations of poetry.

What we need is a secular Vergil to guide us deeper into the sunlit hell we’ve made of the 21st century. If he does his job well, and we are truly paying attention, we should be able to find our own way back once the tour is over.

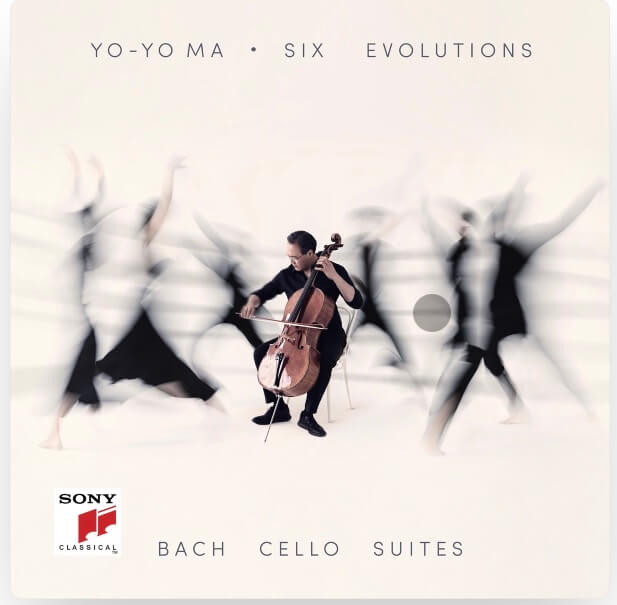

Since I first heard them almost sixty years ago, J.S. Bach’s suites for unaccompanied cello have never left me. Over the intervening decades, I’ve listened to I don’t know how many recordings of them — by Casals, Fournier, du Pré, Rostropovich, Ma — and now that the Internet has finally delivered us up to the celestial jukebox as promised, hardly a year goes by without some new rendition to attend to.

This is a profound thing, an almost too good to be true thing. Play these at Rush Limbaugh’s funeral, I find myself thinking, and the world, for a moment at least, would be a better place.

Such things don’t happen, not in the public space we’re compelled to share with the vengeful, but in private we can reflect on what it is that makes us compassionate even when we know the worst about ourselves. For those private moments, I can think of no better soundtrack than these genuinely sublime compositions of Bach’s, and no better argument for their right to be called that than Yo-Yo Ma’s latest recording of them.

His phrasing here is revelatory, the dynamic range astonishing, the pacing as intense and as variable as one imagines Bach must have heard it in his own inner ear. There are bones and sinews in these performances, and no apologies. As the Italians say, they sing — so much so that I find myself wondering if I’ve ever before heard these pieces played this well, this architecturally. Even Ma’s own earlier recordings of them seem somehow less forceful, less transparent. This is very high art indeed, and I for one am grateful for it.

And if you had

What you thought you had

When the trees

Turned with you

And the times

Out of all time

Came

And you could see what they said

What they all of them said

Was true

No measuring here

No defense necessary

Sing with me now

No iron intrude between us

Break your vow here

And no fire burns

The way we burn already

The living and the dead

Together

Cold fire

Even when

the lot of us

are ash

I will tell you

Did you think that I’d

Forbear to tell you

How we are?

How

Broken by the knowledge

Broken

All the pieces find

Their voices here

Speak here

Thigh-deep in lupine

Dead-white

Cypress arms and fingers

Over us

And our eyes on the gull

This was written at the invitation of the founder of a Web site which unfortunately never saw the light of day. Waste not, want not, right?

A House Divided: Can Independent Thinking Flourish in the No-man’s Land of the American Culture Wars?

When I was asked recently if I thought that our increasingly vicious culture wars were stifling independent thinking in the United States, my answer was an immediate and unqualified no. Now that I’ve had time to consider the question a little more thoroughly, my answer is still no, but I no longer believe in dismissing out of hand the concerns which originally prompted it.

The truth is that human beings, those at any rate with the spirit and the leisure to work at puzzles or dream dreams, are always going to think what they think, regardless of whose agents are looking over their shoulders, or what orthodoxy of the moment is threatening to vilify or imprison them. The real question is whether or not all this thinking can have any lasting effect, beneficial or otherwise, on the civilization which spawns it.

Despite the several centuries which have passed since the first impact of the Enlightenment on our epistemology, this is still an open question. For all the recent furor which they’ve created in the United States, the culture wars declared by the right have in fact been an epiphenomenon, an engineered distraction acting not so much to prevent independent thinking per se, as to prevent that thinking from entering our political discourse, or finding expression in the policy decisions of our government. In that, of course, the right has until very recently been remarkably successful. Its success, however, has come at a price.

That price is blindness. The enemy of conventional wisdom and the status quo, and of its die-hard defenders, has never been the free-thinker, but reality itself. You can imprison the advocates of inconvenient discoveries, but you can’t imprison events. When the Spanish Inquisition institutionalized the search for heretics, and industrialized the lighting of autos da fé all over the country, smart people found a home in Holland, or England, or in the New World, and Spain entered a long decline which persisted, in one form or another, until the death of Franco. More recently, the fan dancers of unfettered capitalism have held not just the usual rubes in thrall, but our policy makers and soi-disant intellectual elites as well. Then, quite unexpectedly for them, reality turned up the house lights and set fire to the fans. Suddenly, we’re once again talking publicly about the responsibility of governments to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common Defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity.

Even if you accept, as I do, that politics broadly defined is the only effective instrument for mediating which ideas will become the currency of the realm, and which will be relegated to bric-a-brac in the museums of memory, it’s clear enough that no matter the necessities of human nature which force us to rely on politics for this mediation, there can be no blunter instrument for the purpose, nor any which affords us less comfort in the wielding.

Tyrannies are real enough, after all, and so are the ideologies which give rise to them. Even if you have confidence that they can in the end be overcome, the millions slaughtered and enslaved by them in the 20th century, beginning more than a hundred years after the Declaration of the Rights of Man, must give an honest person at least some pause to question that confidence. George Orwell understood this, and in 1984 presented us not only with a haunting butcher’s bill for the previous half-century’s devotion to armed isms, but also a warning that by adhering to them, we were flirting with an end to history, and not a happy end at that.

I found 1984 profoundly disturbing, but I remain an optimist nevertheless. Orwell was prescient in many ways, but in the end, his inner Jeremiah outmaneuvered his sense of history. No boot, however determined, however well-funded, can stamp on the human face forever. Other boots may in time come along, but they will always have to take their turn, and then, inevitably, pass into oblivion. There is such a thing as the dialectic, after all, even if, after all these years, its nature is still to a great extent a matter of debate.

That debate has interested me ever since I first discovered it as a young man. Even when I was still a child, the dynamics of my family were such that I quickly developed grave doubts about the sufficiency, if not the necessity, of a rational approach to problems, as well as a perpetually nagging curiosity about why what I was told, both by my elders and my peers, was so frequently at variance with my own experience.

Perhaps that is actually why, more than forty years ago, I went to hear a public lecture by Herbert Marcuse on the campus of UC Berkeley. At the time, it was the hottest ticket in town. Ronald Reagan had already accused Marcuse of trying to make communism safe for undergraduates — in the catechism of the right wing, the moral equivalent of dispensing poisoned candy to children — so of course the lecture amphitheater was packed, and not just with those who’d read his books, but also with the rebellious, the curious; all those passionate advocates of generational solidarity who were already fashioning the Sixties into either a revolutionary epoch or a silly season, depending on how you judged the culture wars which were already underway.

I don’t know what any of us expected, but what we got was an elf — a slight, decidedly unheroic looking man talking to several early arrivals in the pit below the stage. Already nearly seventy, he didn’t look it, except for the almost white hair cropped close over his ears. Very professorial, very European, I thought, yet as informal in dress and manner as his audience. Once the last of the late arrivals had arranged themselves around the edges of the room, and the sponsors had managed, with a flurry of hand waving and restrained begging, to quiet the crowd and make their introductions, the old man skipped up the steps to the stage, walked over to the rickety podium, and started to speak.

Most of what he said that evening I no longer remember. I was, in any case, already familiar with much of it from reading Eros and Civilization, and One-Dimensional Man. What I do remember, though, what has in fact stuck in my mind from then until now, was his opening line:

As I often seem to be doing these days, I shall begin with Hegel…and I shall end with…love.

Like Professor Marcuse, I also began with Hegel, and like the good professor, I very much doubt I’ll end up in the promised land. No one should assume, however, that I don’t believe it exists, or that, somehow or other, love will prove the key to getting there. I know very well that independent thinking, and thinkers, aren’t immortal, but they are eternal. All you have to do, if you want confirmation of that seemingly bold assertion, is to stop for a moment and walk away from the megaphones.

Businessmen say going forward instead of in the future. Our Secretary of State says that Muammar al-Qaddafi must acknowledge what the International Community requires of him. A respected liberal economist, defending the necessity of nuclear power plants, remarks that it’s unlikely that the Chernobyl accident produced more than 50,000 excess deaths world-wide. He seems to take it for granted that this simple statistic will rekindle our faith in Atoms for Peace.

Why does no one in public life sound like this any more?

It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces, but let us judge not, that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered. That of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes. “Woe unto the world because of offenses; for it must needs be that offenses come, but woe to that man by whom the offense cometh.” If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to Him? Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.”

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

The wizard can bare his breast to the assassin’s dagger without blinking, and the Son of God can carry his own cross with confidence to Calvary because their mortal forms are mere teaching points. Abraham Lincoln understood this in a way that our present leaders do not. Secure in the vast powers at their disposal, they seem to have forgotten that they’re nevertheless as mortal as the rest of us, and that, in the end, their powers are only on loan to them. We can’t afford such a luxurious forgetfulness; we have to deal with the consequences of their actions every day. It wouldn’t hurt, I think, to remind them of that fact from time to time.

*The wizard confounds death — from the 1981 fantasy film, Dragonslayer — a wonderful bit of whimsy, part Sorcerer’s Apprentice, part Arthurian legend. This line is spoken by no less grand a thespian than Sir Ralph Richardson himself, in the role of an old wizard with a flair for Shakespearean declamation even in Latin.

These are difficult times. If you squint a little, you might just be able to make out a grave and solitary figure above us on the battlements, watching the distant consequences of his folly approach.

President Bush? Many of us would like to think so, but that would be far too convenient. Even Democrats have to admit that there’s been no shortage lately of fools and knaves from both parties at work in Washington. No, our sentinel doesn’t have or need a name. It’s the image of a collective apprehension; you might even say that it represents America itself.

The impulse to blame someone or some thing for our predicament is natural, but the sad truth is that it doesn’t matter whether the mess we’re all in — the collapse of global finance, the increasing disparity in incomes, the interminable war on terror — is the result of something we did, or of something that was done to us. What matters is that there will be serious consequences for all of us. We desperately need some clarity about what we can do to avoid being overwhelmed by them.

Unfortunately, what we’ve been hearing so far from both Republicans and Democrats is what we can’t do. We can’t close Guantánamo, not really. We can’t try the people we’ve held and tortured for years, nor can we release them. We can’t withdraw our troops from Iraq or Afghanistan, not all of them, anyway — not for years and years. We can’t let the large investment banks fail, not unless we want them to take us with them into oblivion. We can’t have universal health care — not unless the so-called health care industry gets its cut off the top. We can’t, in short, make fundamental changes in anything. No alternative to the status quo is credible, let alone politically feasible, even though the status quo is arguably what got us into this mess in the first place.

Can this possibly be true? Simply put, no, it can’t be. Anyone who’s watched the implosion of the Republican Party over the past two years must realize that even seemingly unshakeable convictions have to yield to reality eventually, if reality insists — and reality always insists, particularly when it’s in fundamental conflict with those convictions.

This is what makes clowns of would-be prophets like Rush Limbaugh or Newt Gingrich. They don’t see reality, even that small part of it which is given to wiser mortals to see. In fact, they can’t see it; they’re too busy collecting underpants and grinding axes.

At this point in our history, I think that we can safely ignore the clowns, clowns like Limbaugh and Gingrich in particular. The more difficult task is to engage our elected representatives and their list of can’ts. After all, we did put them where they are, and up to now we’ve been willing to accept their assurances that they’ve been acting in our best interest.

We’d do well to begin by ignoring their assessments of what is and isn’t possible. While it’s true that reality always sets an upper limit to our aspirations, and must be respected, it’s also true that what we can do is always at least partly a matter of what we want to do, so long as what we want to do takes honest account not only of our present circumstances, but of our history as well.

———

And what of that history? Despite the pieties we’ve all had to endure on patriotic occasions, we’ve always been citizens of two Americas; the America dreamt of by what Lincoln called the better angels of our nature, and recorded in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, and that darker America best described in our own time by Noam Chomsky — the America of slavery grudgingly relinquished, the America of a cruel, century-long war on our aboriginal peoples, the America of Commodore Perry’s threats to the Japanese and William Randolph Hearst’s threats to the Spanish, the America of the Homestead steel strike and the Manzanar internment camp.

More recently, roughly from the end of World War II to the present, managing this dual citizenship has been easier for most of us than we deserved, largely because we’ve been isolated enough, and secure enough, to avoid reflecting on the incompatibilities between the two. Only when something seriously unpleasant happens to us, and we’re actually forced to confront those incompatibilities, do we encounter what you might call the hidden surcharge of American mythology.

It appears on the bill as confusion, this surcharge, and even the most privileged among us — senators, defense industry CEOs, Wall Street bankers and the like — have to pay it. The cognitive dissonance so evident in our present political discourse has all sorts of ancillary causes, but its roots lie in the fact that we believe things about ourselves which aren’t true, and haven’t ever been true except when expressed — and acted upon — as ideals.

We had to destroy the village in order to save it. They hate us for our freedoms. The government is obligated to honor the bonus contracts at AIG, but not the union contracts at General Motors. What are statements like these, if not evidence of a dishonest and self-serving logic at the heart of our national conversation, yet how many of us listen to the like every day without so much as blinking? Whether we realize it or not, such dishonesties are and will likely continue to be the principal impediment to the future we’ve all promised ourselves, and have been promising ourselves since the founding of the Republic.

———

The government will do what it likes, of course, at least until we can get our hands on it again. In the meantime, those of us who can actually see Birnam Wood on the move must ask ourselves a question which has been asked many times before in our history: What is to be done?

First and foremost, America must publicly, and unequivocally renounce its pretensions to empire. Phrases like Leader of the Free World, Axis of Evil, Regime Change, Global War on Terror, Extraordinary Rendition, Enhanced Interrogation, and Full Spectrum Dominance must disappear from our foreign policy and military vocabularies, and the attitudes which gave rise to them must be censured.

Other countries, even small and weak ones, don’t belong to us. We have the right to ask them to respect our legitimate interests, as well as the right to defend those interests, even by military force, if they are attacked, but only so long as we understand that others have the same rights, and that we have a duty to respect their rights even as we demand that they respect ours.

We have absolutely no right to threaten the legitimate interests of other countries merely because our military superiority permits it. Neither do we have the right to fund opposition parties in their elections, train expatriate paramilitary forces and send them, along with CIA and Special Forces of our own, to overthrow their governments, assassinate their leaders, and kidnap their citizens off the streets of neutral countries and send them elsewhere to be tortured. Above all, we have no right to bomb or invade another country merely because we have the power to do so.

The United States government has done all of these things in the past. We must not allow it to continue doing them in the future.

We must also demand to know why it is that the national defense, properly defined, requires a dozen nuclear-powered aircraft carriers and the combat and logistical support vessels which accompany them. Why does it also require some 700-odd military bases outside the continental United States, some of which have been acquired by forcibly transporting their indigenous populations? (Diego Garcia, Bikini Island) What purpose is actually served by fourteen nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines, with a combined armament of hundreds of thermonuclear warheads?

We must renounce empire not only outside our borders, but within them as well. We must remind our elected representatives that the government is not in business for itself, and that the national interest is not defined solely by geopolitical advantage or corporate commercial interests. When lobbyists come to their offices, checks in hand, they must remember who they’re pledged to serve.

There’s something desperately wrong with a representative democracy, I think, when its elected government consistently enacts laws and sets policies with which the majority of the electorate disagrees, when it spies on its own citizens without affording them the protections supposedly guaranteed by the Bill of Rights, imprisons them without access to habeas corpus, and uses their own taxes to propagandize them — all of which our government has done, and continues to do.

Secondly, the American people have already paid for a very expensive, and very competent scientific establishment. We must demand that the fruits of its research be respected, and consulted whenever they might be of benefit in resolving a debate about public policy issues.

The potential danger of global warming, for example, and its origin in carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuel combustion, represents an established scientific consensus which ought not to be ignored simply because it may have a negative effect on existing corporate profit margins, or offends the superstitions of the ignorant. The government must tell us why, given what we know about global warming, it still chooses to invest in military and diplomatic initiatives from Kyrgyzstan to Georgia, not to mention two wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and a potential third one with Iran, all of which, despite its contemptuous denials, seem principally dedicated to the defense of oil and gas pipelines which, for the most part, haven’t yet been built, and may never be built. For what reason is that investment preferable to investing in solar power development in our own Southwestern deserts?

The systemic threats posed by an industrialized agriculture are also well-established. Closely-confined livestock in large operations act as a breeding ground for new human pathogens, and the waste-lagoons from these operations have also been shown to result in e-coli and salmonella contamination of natural watersheds, streams and nearby crop fields. We must determine whether or not this can be fixed; if it can’t be, we must demand that these practices be ended, and replaced by others which are sustainable.

Cash crop monoculture in developing countries has often resulted in the destruction of subsistence economies, replacing them with a pernicious economy of imported consumer goods restricted to the elite classes, which are typically composed largely of officials of the governments responsible for negotiating the contracts with the agricultural corporations in the first place. We must demand a cost-benefit analysis of such practices which is untainted by the influence of their corporate sponsors, and end them if their benefits can’t be proven, or if proven, can’t be more widely distributed.

The possible danger of genetically-altered crops to human health as well as to the gene pool of existing crops, and to the insects which pollinate them, is difficult to assess because of laws which protect the proprietary interests of the corporations which hold the patents to them. Such laws must be altered to reflect the public interest in knowing the consequences of genetic modifications to our food supply.

Finally, we must address the increasing inequities and injustices in the way income is distributed in America. It’s been said that the genius of capitalism lies in the creation of wealth, not in its distribution. This once made a certain amount of sense, I suppose, back when Pittsburgh’s steel mills were still belching smoke, and industrial unions were beginning their wars with a previous generation of oligarchs, yet the Sears Roebuck catalog still continued to arrive without fail every Spring, complete with a tantalizing new compendium of accessories for that Model T which everyone in rural America was presumed to have in his garage or his barn. Nowadays, looking at the current state of financial capitalism — not just in the United States, but worldwide — this particular nugget of conventional wisdom is beginning to look more and more like a gross oversimplification no matter which way you come at it.

Where to begin? We must demand the restoration of a genuinely progressive income tax, paying special attention to increasing the marginal tax rates on the wealthy. We must make prudent, but substantial cuts in the military budget, and close the revolving door between the Pentagon, the defense industry and the Congress. We must also adopt and fund a single-payer health care system, reform the unemployment insurance system, and substantially increase the minimum wage.

The Fair Labor Standards Act must be strengthened, and we must see that it’s enforced. The Employees Free Choice Act must be passed. Large banking conglomerates must be broken up, and we must insist on transparency in hedge-fund transactions, as well as the right of the government to regulate all financial derivatives, not only those which exist now, but also those which are yet to be invented.

We must also restore and fully fund our public education system, including federal support for low-interest loans for college and university students. We must replace our current welfare system with one which is both sensible and humane. Supplemental funding for both systems must be taken from general tax revenues and administered by the federal government, even though basic funding may come from local and state governments, and the programs themselves may be administered locally. (If religious organizations want to force the poor to sing hymns before feeding them, they should do it on their own dime. If they want to teach Intelligent Design and abstinence instead of evolution and sex education in the classroom, let them pay for their own classrooms.)

We must initiate serious attempts to address the problem of outsourcing, and of free trade agreements which tend to increase the income of workers elsewhere (a good thing) but also, inevitably, reduce the incomes of our own workers (not a good thing.) This seems to me to be a problem which we can’t hope to solve without genuine international cooperation. Perhaps we should think of founding something like a Fifth International, and inviting the participation of governments and global corporations, as well as workers’ organizations from around the world.

Investments in forward-looking infrastructure projects, such as mass transit, solar power and ugraded electrical transmissions systems, universal broadband, reduced carbon-footprint manufacturing, and local attempts to come to terms with urban sprawl, must be put on the government’s agenda, and we must see that they are taken seriously.

———

All of this, of course, is only a beginning. There are other issues to be explored, other patterns to be documented. — immigration, for example, or sustainable growth, or the war on our underclass represented by our current drug laws.

There’s also the matter of how we should go about doing what we need to do. That’s a subject for another day, I think. For now it’s enough to say that you can’t solve a problem without correctly identifying it, and you can’t speak with any real assurance of your rights and responsibilities until you know who you are.

Karl Marx once wrote that Religion is the opiate of the people, and virtually every book of fundamentalist talking points used to mention it at the beginning of a long screed about Godless Communism. What they didn’t realize, what few Americans of any persuasion seemed to realize, is that proverbs like this made Marx as much a true child of the Enlightenment as Thomas Jefferson or James Madison, who might well have agreed with him in private, if not in public.

Things are more complicated now. Thanks to post-Enlightenment developments in psychology, sociology, advertising, agitprop and the like, we now have an entire range of opiates to choose from, from the original one, religion, to consumerism to…well…opiates themselves — the nasty, illegal kind that you can snort, smoke or inject while scrupulously avoiding your duties as a citizen. If we genuinely want to live in a free country, rather than just faking it by, say, waving a flag on the Fourth of July, we have a lot of work to do. If we really want to avoid Macbeth’s fate, we’ll have to be nimble about it. There just isn’t any other way it can be done.